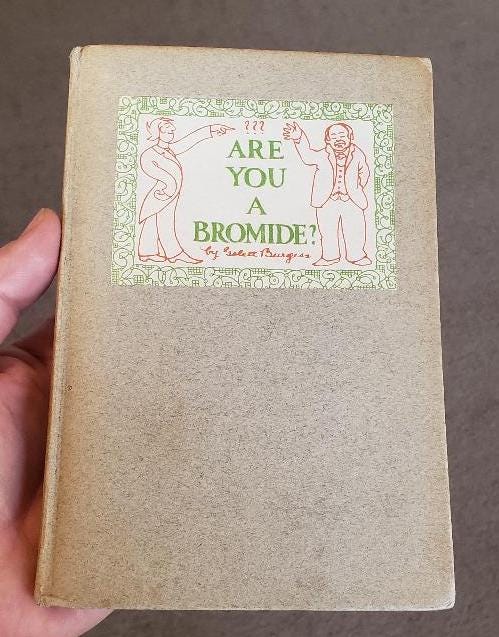

Are you a Bromide?

I picked up this old, very small book at a used bookstore.

“Are you a Bromide?” it said on the cover. Nothing else. It was like Victorian clickbait.

Curiosity piqued. Was I a Bromide? What is a Bromide? It was not a chemistry book.

I opened it up. It was talking about Bromides and Sulphites, but in the context of social philosophy.

Are You a Bromide? is a scathing critique of the types of people that this author doesn’t like, and seemingly the written origin of the adjective “bromidic” to mean trite or cliché.

Thus, the author example, calls out people that use clichés:

It must be borne distinctly in mind that it is not merely because this remark is trite that it is bromidic; it is because that, with the Bromide, the remark is inevitable. One expects it from him, and one is never disappointed. And, moreover, it is always offered by the Bromide as a fresh, new, apt and rather clever thing to say.

He describes the Bromide some more:

If you both happen to know Mr. Smith of Des Moines, the Bromide inevitably will say:

“This world is such a small place, after all, isn’t it?”

A Bromide might also say

"It isn't so much the heat... as the humidity...."

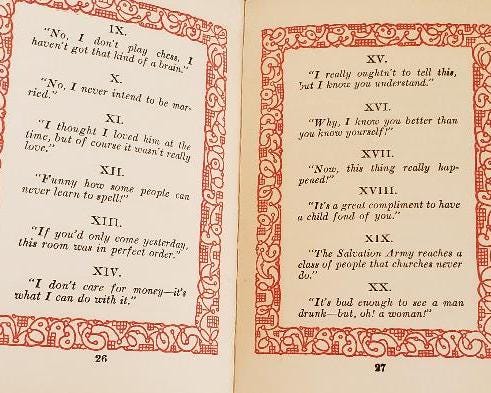

The best part of the book, I think, is when he goes on to list more than forty things a Bromide would say, but a Sulphite (a cool person) would supposedly have no need to say, such as:

“I don’t know much about Art, but I know what I like.”

“You’ll feel differently about these things when you’re married!”

“It isn’t money, it’s the PRINCIPLE of the thing I object to.”

Okay, fair enough. But some are so broad, and others so specific, it seems as if his intention was to label every single one of us a Bromide. For example:

“Yes, but you can live in Europe for half what you can at home.”

“I haven’t played a game of billiards for two years, but I’ll try, just for the fun of it.”

A Sulphite, on the other hand, he says, is of a better class and knows that some of those things are better left unsaid, apparently:

Sulphites are agreed upon most of the basic facts of life, and this common understanding makes it possible for them to eliminate the obvious from their conversation ... They are aware that heat is more disagreeable when accompanied by a high degree of humidity, and do not put forth this axiom as a sensational discovery.

I do wonder, though, wonder how many times he’s heard one of these phrases because someone was simply trying to be polite.

You see, we all like to think we’re Sulphites. When someone comments to us about the weather, we think they’re being Bromidic. When we comment about the weather, we think it’s to be polite and please the Bromide. But maybe that’s what the other person is thinking, too?

We like to think we’re independent thinkers who aren’t like “the masses”. However, because we all think this, that, ironically, makes us all exactly like the masses, I’d say.

In fairness, the author does touch on the more subtle shades and contradictions of the theory.

I have to admit, I found this book pretty funny at times, in the same way I enjoy Curb Your Enthusiasm. The indignation people have about others’ behavior (especially while ignoring their own) can definitely be amusing.

The book was written by Gelett Burgess, the American author, humorist, and publisher who was a well-known critic in the art world in the late 19th Century.

You can read the whole thing right here on Gutenberg.

Poem of the week

Happy the man, and happy he alone,

He who can call today his own:

He who, secure within, can say,

Tomorrow do thy worst, for I have lived today.

Be fair or foul or rain or shine

The joys I have possessed, in spite of fate, are mine.

Not Heaven itself upon the past has power,

But what has been, has been, and I have had my hour.

—John Dryden, Horat. Ode 29. Book 3. Paraphras’d in Pindarique Verse, 1685